Proposed new mining industrial manslaughter legislation in Queensland has recommended up to 20 years in prison for mining managers and supervisors found guilty of negligent conduct involving the death of an employee. Mining companies would receive maximum fines of up to $13.34 million.

But many across the mining and resources industry are questioning the motives of the Queensland Government which is seen to be looking for a silver bullet to appease public anger over the recent spate of fatalities across the industry, including the recent death of mineworker Brad Duxbury on Monday night.

Brisbane’s Courier-Mail revealed that a draft bill proposing industrial manslaughter provisions included in the Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health Act and the Petroleum and Gas Act has been circulated around stakeholders in the mining and resources sector for consultation over the past month. Comments on the bill closed Monday this week.

While Industrial manslaughter isn’t new to Queensland, having been passed into legislation for general industry in October 2017, there are many critics of industrial manslaughter legislation and its potentially damaging effects on disclosure by workers across the industry.

David Cliff, Professor of Risk and Knowledge Transfer at the Minerals Industry Safety and Health Centre spoke recently on the aspects of industrial manslaughter. “Industrial manslaughter is a complex question. If you bring in a big stick to frighten people into vigilance, the negative perception of that stick will have a detrimental impact on health and safety because people become unwilling to share what happened.”

“From a commercial point of view,” he added, “when people are afraid of prosecution it will become increasingly hard to recruit and re-train employees because they will perceive the role as holding risk to them.”

Cliff urged caution because information sharing could simply dry up. “There is a culture of openness which sees information about fatalities being shared so we can learn from our mistakes. The new industrial manslaughter law risks that not being as open as it has been in the past.”

“People like simple solutions, they like silver bullets,” he adds. “But we are now in a safety culture maturity phase where we have all the easy wins, and we need to take a deeper look at the fundamental causes.”

Industrial manslaughter may be seen as a panacea for mine deaths

Hard evidence on the success of industrial manslaughter legislation to deter reckless conduct is simply not available, at least in Australia.

The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) introduced industrial manslaughter legislation in 2004 under the Crimes (Industrial Manslaughter) Amendment Act 2003. The ACT law seeks to prove that a corporate culture existed within an organisation that directed, encouraged, tolerated or led to noncompliance with the law, whereupon the fatal event occurred.

After 14 years in operation, there have been no successful prosecutions in the ACT. In fact, not one case has proceeded thus far.

Queensland has also previously launched prosecutions under Industrial Manslaughter, but to date, a conviction has not been achieved.

Reckless conduct must be proven

Under Industrial Manslaughter legislation across Australia, the concept of ‘reckless conduct’ and negligence generally must be proven in court for the industrial manslaughter case to be successful.

Proof associated with reckless conduct tends to be somewhat challenging for prosectors. They need to prove to the Court that the accused:

- engaged in reckless conduct;

- that their conduct was voluntary;

- that it endangered the life of another person;

- acted recklessly; and

- acted without lawful authority and excuse.

Of course, the wash-up of the extension of Industrial Manslaughter in the sector may see variations to the above, but in essence, Industrial manslaughter legislation has largely been a toothless tiger.

Government grasping for solutions

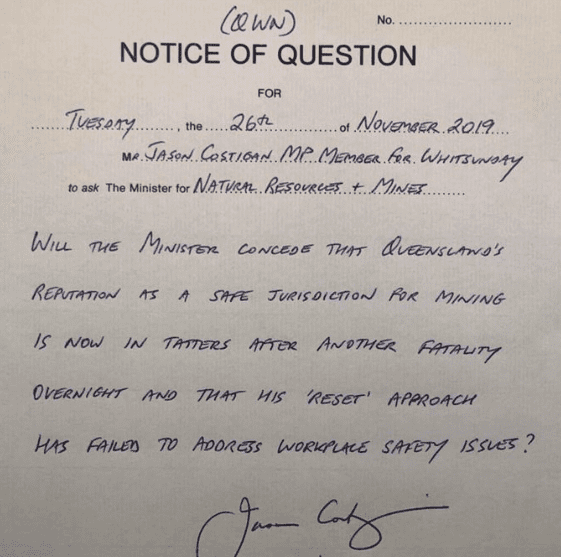

The Queensland Government’s leak to media regarding the implementation of industrial manslaughter in mining has been timely in light of the death on Monday night and questions raised in Parliament by MP Jason Costigan yesterday.

The Queensland Opposition’s Dale Last said this week that “We need to get to the bottom of what went wrong in this incident and in the other incidents so that we can address the issues and make our mines safer.”

“In August I moved a motion to establish a Parliamentary Mine Safety Inquiry and I stand by that call. Surely, the current government must put aside politics and get to the bottom of these incidents once and for all.”

“The Mine Safety Resets were one way to address safety but, when people’s lives are at stake, we shouldn’t limit the investigation and, as a parliament, you would like to see cooperation.”

“We need the input of workers and people with experience in mines and quarries, not bureaucrats from Brisbane.”

So many unanswered questions in mine safety

The Queensland Government’s response to the spate of accidents, including safety resets, the establishment of a mine safety body and now industrial manslaughter legislation may have some effect on mining safety in the state.

But with 11500 high potential accidents occurring across the state since 2013/2014 and around 1900 last year, on the basis of probability, there will be another disaster looming very soon.

Introduction of industrial manslaughter legislation in Queensland may appease the general population, but it will do little for those who have recently buried their loved ones as a result of a mining accident.

Read more Mining Safety News