We recently spoke with Craig Dickson, an organisational consultant and motivational speaker who has been at the coal face supporting some workers through the Middlemount mine fatality.

Craig holds Masters degrees in Psychology and Counselling and he has kindly shared his thoughts on the need for change in the industry. Craig discusses the need to respect the value of individuals within the industry and acknowledge that we aren’t all wired in the same way when it comes to dealing with the loss of a co-worker.

Craig writes….The ultimate purpose of this article is to ensure that something positive comes out of the utterly tragic recent mining fatality at Middlemount in Central Queensland.

I write this with the utmost respect for the deceased’s family and with the intent to raise awareness of the need to support and develop people in the mining industry, regardless of their roles and positions, as well as challenge the stereotyped understanding of what mining employees’ needs are, who they are and what they experience.

Looking at response actions to traumatic experiences and the need to improve this to promote post-traumatic growth is a focus, as well as a brief discussion of what has been scientifically proven to develop and drive sustainable successful outcomes for employees and organisations in mining and other industries in a win-win and reciprocal manner.

The phone call that you don’t want to have

The journey of life involved me in the recent tragic loss of a miners’ life at Middlemount mine site, where I had been working periodically for the past 2 years. I was at home working when I received a phone call from the Queensland Manager of the onsite maintenance plant at Middlemount.

The recollection of the phone call was along the lines of could I “come out and help out our men with what has happened”, to which I asked a question to gauge his focus.

I said, “Ok mate, I will aim to come out and help the men to process what has happened and aim to get them back to working effectively as quickly as possible”.

Whilst developing people are always my primary focus, I always want to first understand the desirable outcomes from the leadership who are driving the support.

The response I received was precisely what I expected and in line with methods of genuine people-oriented and values-based Authentic Leadership: “Mate, I don’t give a ….. at this point about production, I just want to make sure that our people are ok”.

Collecting information and striving to understand the people, culture, challenges, psychology, backgrounds, needs and strengths have been of vital importance to the success of my interventions and training and have developed a strong perspective in line with research that may be considered by governing bodies towards enhancing an industry through a concerted focus on developing people, engagement and practices.

Not simply the drive for ‘more’ in isolation from meeting the needs of the people literally at the coal face.

As with all of my dealings within the mining industry, I approached my engagement with a clear intention to help and a curious mindset geared towards being open to what appears and to not try and predict what would present in the experience of the men I would be working with.

Being a learner and observer in a tragic situation

This approach has enabled me to be a ‘learner’ and an ‘observer’ at the same time that I am facilitating professional development seminars or individual coaching.

The qualities encountered in the people through my work training all employees at Middlemount Coal and their associated contractors were values such as authenticity and work ethic, which are generally obvious and expected prerequisites for employment in mining.

However, the qualities that may be less well known to exist within the people in mining extended much further into empathy, compassion, integrity, care and even love, as well as a desire to improve themselves and contribute meaningfully given the opportunity.

A sense of duty to family and self-sacrifice were the most outstanding qualities I encountered and almost universally present.

My previous experiences with this maintenance organisation prior to arrival on site was extensive and proactively designated towards building on and enhancing their authentic leadership, psychological capital, emotional intelligence and communication for example.

I knew that their leadership team understood not only the value in supporting the processing of this terrible event but also the absolute necessity in having all of their men and women provided with an opportunity to share and better understand their experience of it.

It is easy in very challenging times to throw stones at people, practices and systems and feed on emotions or ‘admire the problem’, however, my approach is and always has been around a solutions-focus towards developing people, practices, culture and systems towards removing obstacles to success, building resources and skills for combatting difficult times and, ultimately, practising towards becoming the best versions of ourselves.

I would argue that the development of all capacities such as positive leadership, mindset, success habits and even safety frameworks and approaches, for example, begins with the support and development of each individual in line with jointly constructed values.

In all honesty, even though I aimed to be clear of any assumptions of what may be the experiences of the people on-site and approach people professionally with an open mindset, I still mistakenly posited the hypotheses that individuals may be affected differently according to whether they were on-site at the time, their proximity to the event and/or the depth at which they knew the man.

A deep outpouring of emotions

What I found across the board was invariably a deep outpouring of emotions in line with the significant grief and loss they were experiencing regardless of their relationship to the deceased or whether they were on-site at the time.

‘What if’ questions, reflections on their own involvement in situations that could have been catastrophic, concern for the deceased and the utter despair of his family and the thoughts of the possibility of not returning from work themselves promoted incredibly strong emotions that required validation, expression, support and reframing as was appropriate.

Being heard, being validated as having important perspectives, having their humanity and their mixed emotions explored and understanding the commonalities of experience to all and knowing that it was ‘ok to feel not ok’, proved to be very helpful in unpacking and processing their own reactions and finding a positive way forward.

Proximity to the event and enhanced response responsibilities such as the ERT (Emergency Response Team) exhibited more severe symptoms of trauma and, in my opinion, these people were operating in an elevated state of heightened alertness and responding to the environment even several days later.

Reports online about tardy responses from these early responders were fallacious and cause for concern, as well as potentially very damaging to these people who put themselves in physical, emotional and psychological harm’s way to help.

Being incredibly vulnerable and in need of professional support themselves because of their selfless actions warranted a better level of understanding and support from some writers who could have addressed the situation with more empathy and from a non-blame and ‘do-no-harm’ mindset first.

The ERT response was immediate, professional and selfless with unwavering attention and care towards providing the best possible care for the victim and honouring him in every way that was humanly possible.

This dedication took its toll on many of them and required intensive levels of support that many did not receive adequately at the time and, it is my sincere hope, that processes and practices change as a matter of highest importance to prevent the potential for post-traumatic stress and other anxiety reactions in future.

The requirement to address basic human needs

In normal circumstances that are completely separate from times of crisis, people have basic needs that require addressing for them to operate at any level of normal capacity.

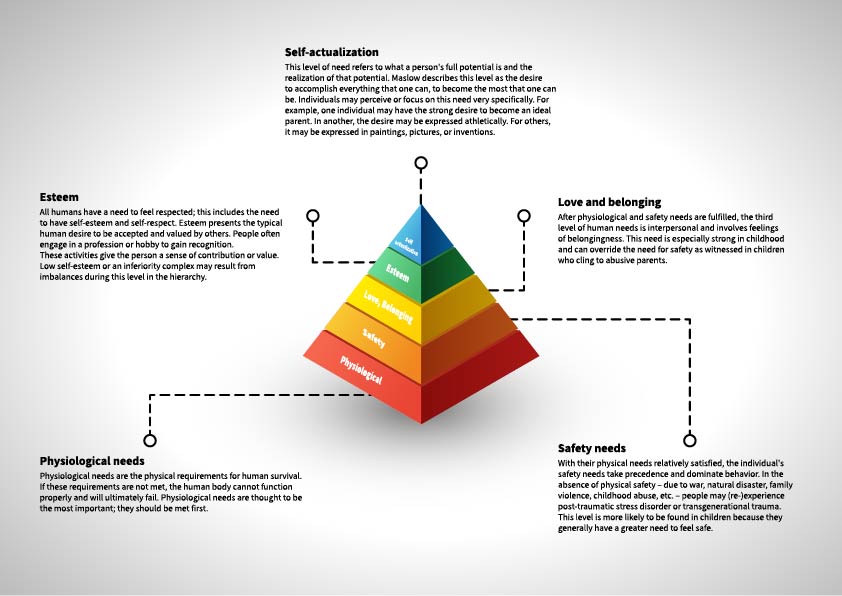

Abraham Maslow, widely considered to be one of the fathers of humanism and positive psychology, created an 8-stage hierarchy of needs that outline human thriving.

The stages are depicted in a pyramid design starting at the very bottom representing the most basic needs, up to the very top which represents what is considered as being the optimum level of human functioning known as self-actualisation.

At the very base of this hierarchy are basic biological needs of food, water and sleep etc and just above this stage are the essential ‘Safety Needs’ of security, safety, order, limits and protection.

Traumatic events heighten the need to feel secure and safe and explicit understanding of the importance of this need could become more widespread across the industry towards providing greater levels of support for those who are bereaved.

Supporting this security need was a primary focus for the leaders of the maintenance crews and enabled them to return to relatively ‘normal’ functioning (less fight/flight activity) and to focus their capacities back onto their roles and responsibilities.

If nothing else, the mining and other industries could become curious about this hierarchy and the associated human needs and seek to address them further, realising that the higher the level that employees’ needs are met, the more that they thrive and improve in other areas of the hierarchy in an interdependent way.

This is not to say that individuals should not seek to meet their own needs and enhance their own lives, as they absolutely should. The suggestion could be that an understanding of these needs and efforts to support them in the workplace can have many positive outcomes for all.

Traumatic experiences also raise very significant questions in all people, regardless of their roles, exteriors, stereotypical presentation and other ‘boxes’ that society has deemed necessary to separate and divide people into.

Miners are renowned as tough and resilient, who just suck it up and get on with it. Basic human needs, however, are blind to these man-made constructs and stereotypes and I have experienced first-hand a real thirst for learning and upskilling towards building capacity to respond to the demands of life at home and at work for example.

It is easy, yet misguided, to dismiss a person’s circumstances, limitations or challenges and just push them to do as they are told and then to expect those very people to produce at acceptable (or above) levels.

It may be fair to suggest that the mining industry covers basic biological and physiological needs of food, shelter and sleep etc (1st basic need) reasonably well and are consistently striving to improve safety and security needs (second stage).

However, I would also posit that helping to meet the third stage (belongingness, strong trusting relationship, connection); fourth stage (esteem needs, achievement, status, self-efficacy) and fifth stage (cognitive expression, meaning and self-awareness) dramatically contribute to enhancing subjective wellbeing, life satisfaction and work engagement, as well as all of the vitally important subcategories inherent in them.

These facts have been found through a plethora of peer-reviewed research and provide nuggets of wisdom and possible direction that, once again, meet outcomes whilst supporting the needs of the most important resource available – people.

Vitally important human needs were evident due to the challenges faced by the people working on the mine site where their co-worker and friend lost his life.

Support in times of crisis

People required appropriate professional support and it is absolute nonsense to expect the vast majority of people in that situation to be able to function effectively without it.

I would suggest that the likelihood of additional social-emotional and psychological problems surfacing in people lacking adequate professional and personal supports would be very high.

By meeting their needs and providing the opportunity to explore their experience in all of its complexities and do so together with their colleagues was incredibly powerful and essential.

Being guided by feedback from people on the ground and how different support options are helping them is an important assessment avenue that requires consideration.

People process information differently and the question of having someone available to talk to may not cut it as people may not what to seek help in isolation, struggle with the dynamic in that helping relationship and require something more.

The notion of having an EAP representative on-site should not be a ‘fix all’ and providing different forums and opportunities to express and understand their experience are important considerations.

The optimum would be to assist people from surviving to thriving, which in turn supports the outcomes that the mining industry is seeking. Helping people to develop an awareness of their own psychology, emotions and purpose for example and apply a raft of success habits and skills to work contexts benefits all.

Understanding ’employees’ as ‘people’

Almost everybody who works in the mining industry could be considered an ‘employee’, however, in aiming to reduce (or ideally put an end to) fatalities and injuries at work, the mining industry could consider substituting the notion of ‘employees’ with ‘people’ and work at developing explicit understandings and applications of what makes human beings thrive and perform optimally.

A mindset shift from a need for ‘more’ and ‘safer production’, to developing a paradigm that treats the meeting of human needs as an equal priority to the pursuit of effective mining production, may prove to be an important area for investigation.

Astute leaders could consider this as being good for people and good for business. This is not to suggest that people become either ‘new age’ in their thinking and engagement with one another, nor is it to suggest that ‘free hugs’ and going for long walks with one another are the answers.

Developing a positive psychology of success that informs a psychology of safety and sustainability may be considerations that are long overdue.

The statement of equality of outcomes and balance between an outcomes-focus towards ‘Safe Production’ could take into account the SCIENCE of what develops ‘Productive People’.

The benefits of engaged and happier people are contagious and meta-analysis encompassing over 1.9 million people from around the world in one study (See Gallup, 2016) highlight the crucially important correlation of employee engagement to improvements in safety, profitability, productivity, discretionary effort and absenteeism to name a few.

Organisational scholarship, organisational support, effective leadership development and practices and the subjective wellbeing of employees are other intensively researched and validated areas that warrant immediate consideration.

Whilst this is not an academic report, the concept of work engagement is characterised as the investment of multiple dimensions (physical, emotional, and psychological) and a connection with work on multiple levels, whilst organisational scholarship is an extension of positive psychology that emphasises the development of employees’ psychological capital and companies creating positive work life and performance. Subjective wellbeing, leadership development and organizational support are self-evident.

Change can be difficult, particularly when changing paradigms and it could be a time that the mining industry leads many other industries in its management, development and support of the most valuable resource – the people.

People deserve appropriate supports in response to incredibly difficult challenges. These very human qualities require very human responses and support to address the needs presenting and, whilst that may seem a little ‘syrupy’ or ‘soft’ in nature initially, these responses were found to be of great benefit to individuals and, ultimately, the maintenance organisation at Middlemount.

Expecting people to perform without appropriate supports in these contexts is to expect people to be robotic and machine-like.

Perhaps less common questions could be asked of the mining industry, along with other large corporations, industries and systems, as to whether or not they are:

- Organised to assist all people (executives, front line management, operators etc) in identifying, developing and applying their particular strengths, as well as the areas that they had not recognised in themselves as possible problems (blind spots and areas for development) through seeking and receiving constructive feedback?

- Developing awareness around practices, processes and information that may be available to enhance outcomes from a stage of unconscious incompetence (‘don’t know what we don’t know’) through to accepted norms of best practice that happen automatically (unconscious competence) and become self-correcting mechanisms?

- Developing communication styles, coping mechanisms, emotional intelligence and other ‘soft skills’ that enhance outcomes?

- Developing individuals’ psychological capital in line with important implicit and explicit jointly agreed upon values, goals and vision?

- Contribute to employees’ job satisfaction, subjective wellbeing and work engagement, as well as the greater good?

Supporting people sometimes viewed as ‘lost production’

Opportunities to support the needs of people and develop staff have often been viewed in terms of lost production, where, hopefully in the not-too-distant future, these opportunities can be mandated as ways of building capacities to respond and values-based work cultures that promote discretionary effort, heightened work application, team collaboration and contribution that enhance positive organisational outcomes.

For people on-site, having more connected and aligned teams and a ‘circle of security’, meaningful pathways and improved capacities and skills to manage the demands and challenges of working away are of enormous importance and benefit them, their colleagues and their employers in a perpetuating cycle.

In a time of utter despair for the bereaved families of people who have been tragically lost whilst at work in Queensland mines, perhaps new ways of focusing on, developing and supporting ALL people in challenging and, often, isolating work environments such as mining can help build more sustainable and supportive practices that emphasise both basic and advanced human needs.

Horrific traumatic experiences require appropriate supports and care that promote healthy psychological functioning in individuals towards developing greater meaning and hope for the future, whilst also acknowledging the tremendous emotional upheaval that can occur when connected to trauma across various degrees of separation.

In essence and, at the risk of stating the obvious, it is not normal to go to work and not return home from it and this absolutely impacts adversely on people.

The greatest and most significant message that requires reiterating is that through caring for people and investing in them in recurring proactive ways, as well as in times of crisis, employees, industries and organisations have been proven to thrive in sustainable and safe ways.

Read more Mining Safety News